The paths of glaciers are marked by large erratics.

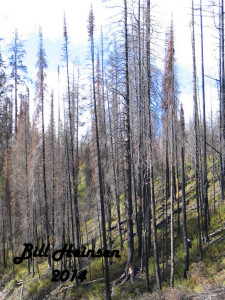

As with the plants, animals vary according to altitude. Only the very hardy, like the mountain goat, mountain sheep, pika, marmot, grizzly bear and the ptarmigan comfortably exist at the high altitudes. With closer examination, many kinds of insects are found.

To follow the path of the river is to traverse time itself. Ancient layers of sandstone and limestone in the Front Ranges give way to more recent prairie soils, a legacy of the great ice sheets that blanketed all of Central Alberta for millions of years. The melting of those glaciers is relatively recent in terms of the great time spans that shaped the Earth. As recently as 15,000 years ago, the climate was slowly warming allowing hardy species from farther south to invade. Among those species were the ancestors of the people who would become known as the Plains Indians.

Fossils recovered from the limestones of the mountains indicate that they were formed in the bottom of vast oceans, long before the dinosaurs ruled. Millennium after millennium as the continents shifted, pushed into, and replaced each other, forces beyond comprehension slowly lifted the seabed, folding, breaking, and thrusting layers one upon the other, until a high plateau had replaced the sea. The plateau was high enough to be cold, allowing snow and ice to form. During this process volcanoes formed to release the intense heat and pressure from beneath and began building the land that would become the western parts of the United States and British Columbia. Those events did not reach in Alberta, but their effects very profound.

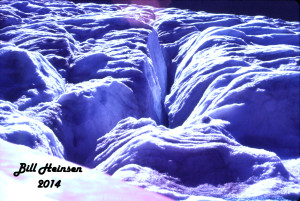

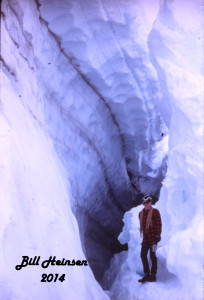

Over the eons, the earth’s climate underwent many changes, climaxing with the last great ice age. Starting about 2 million years ago, glaciers many kilometres thick formed in the higher and northern regions. The weight of the ice caused the bottom to extrude and slowly flow outward from the centre. Grinding and polishing, the ice began to remove the rocky land below. Rivers formed at the perimeters of the glaciers to carry the pulverized rocks away to the oceans in the form of sand and silt.

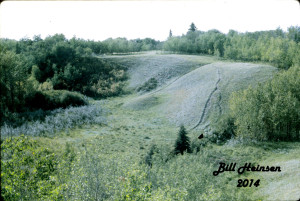

The gap where the Red Deer River exits from the mountains.

Not all sediments were created equally in hardness and strength. Weaker layers gave away to the moving ice faster than did the harder ones. Hugh rifts began to form under the ice. Heat from the friction of ice against rock caused melting and the rushing waters under the ice began to remove more rubble. Water and ice combined to dig deeper and deeper into the plateau, not evenly, but forming deep, approximately parallel gashes. Those deep escarpments would not become visible until the ice had melted and would be called mountains. The Rocky Mountains are a legacy of the Ice Age.